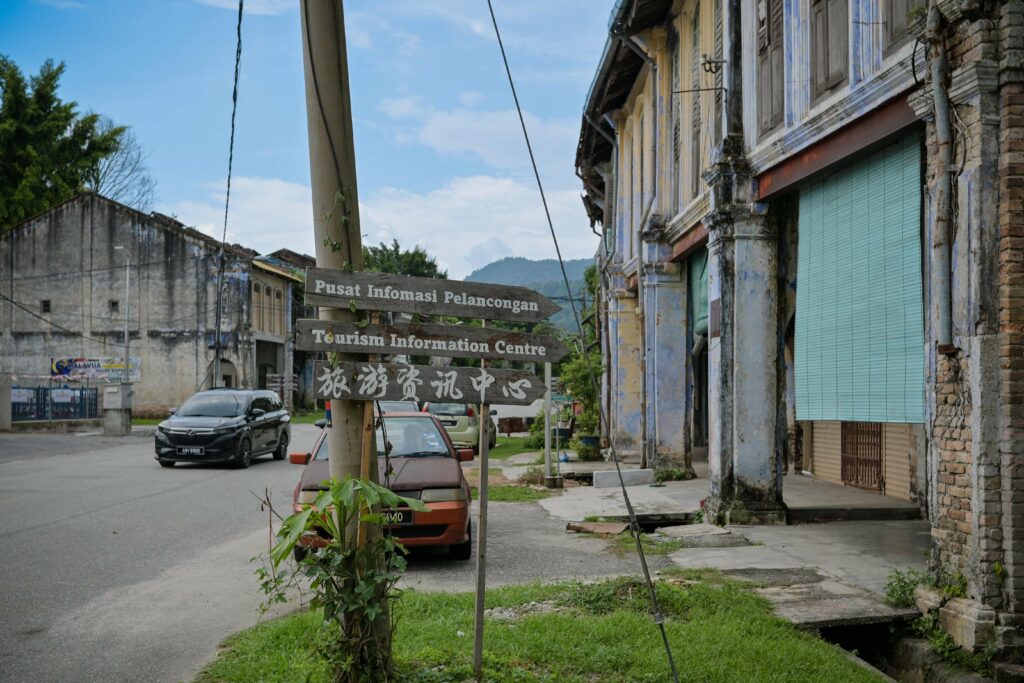

Having visited Galeri Rumah Lat, we went to Pekan Papan, thanks to this article—We were inspired! Although Pekan Papan has been on our wishlist, the recent visit was nevertheless unplanned. On our way back from Galeri Rumah Lat, at the traffic light, we saw a signboard on our left that read Pekan Papan 7 KM. 7 KM only? We decided to go.

Pekan Papan, a small town in Perak, boasts a rich and diverse history that has sadly faded into obscurity. Once a bustling mining centre, it gradually fell into decline due to various historical events and environmental issues.

Papan’s history can be traced back to the 1700s when it served as a lumber town, attracting Malay and Chinese timber workers. The mid-1800s brought a significant turning point with the discovery of alluvial tin deposits, leading to a mining boom in the region.

Following the Perak War and the assassination of the first British Resident of Perak, J.W.W. Birch, in 1875, the British granted exclusive mining rights in Papan to Raja Asal, a Malay-Mandailing chief. The Mandailings originally hailed from Sumatra and had migrated to Peninsular Malaya to escape the Padri War in the 1820s. After Raja Asal’s passing, his nephew, Raja Bilah, took over the leadership.

Under the joint leadership of Raja Bilah and Kar Yin Chew, a Hakka Chinese who introduced advanced machinery to the mines, Papan’s prominence in tin mining grew. This success attracted an influx of miners and diverse ethnic communities. However, conflicts between rival Chinese secret societies, specifically the Hakka-dominated Ghee Hin and the Cantonese-dominated Hai San, led to violent clashes, culminating in the “Papan Riots” of 1887.

From the early 1900s to 1960, Papan played a significant role in Dr. Sun Yat Sen’s revolutionary efforts in China. During World War II and the Japanese occupation, it served as a refuge for refugees and a base for the Malayan Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). In the post-war years, the town’s jungles were used as hideouts for communist guerrillas.

Sybil Kathigasu, a local war hero, operated a clinic in Papan within one of the pre-war shophouses. She and her husband, Dr. Abdon, provided medical assistance to the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army during World War II. The forested surroundings of Papan served as a hideout for the resistance guerrilla fighters they treated.

Sybil’s remarkable courage during the war earned her the second-highest British George Medal, making her the only Malayan woman to receive this honour. Today, her clinic stands as a memorial to her bravery, adorned with newspaper clippings about her pinned to its facade.

Papan today is a mere shadow of what it once was. Once-bustling streets are now nearly empty, and many historic buildings are deteriorating. Despite some preservation efforts, there’s a pressing need to do more to ensure the town doesn’t fade away entirely.

Papan’s history reflects the intricate tapestry of Malaysia’s past. It’s a story of growth and decline, with moments of achievement and tragedy. Even though it has lost some of its former glory, Papan still stands as a unique part of our history and culture, deserving preservation and recognition.

Thank you for reading. After taking all these pictures, 32 in total, it began to drizzle, and soon it rained heavily. Rightly so, because it was already cloudy when we arrived. It was kind of eerie, and thankfully, I met two visitors from an NGO called Persatuan Rejuvinasi Pemikiran Masyarakat.

These two visitors were strolling around near the entrance of Istana Raja Bilah, and I suspected that they were thinking whether to go in or not. So we met and talked and decided to go in together. Had I not met them, I would not have gone to Istana Raja Bilah alone.

References:

Lubis, A., & Khoo, S. N. (2003). Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in Perak, 1875-1911. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA78070926

Malaysian Ghost Towns Series – Pekan Papan. (2023, June 13). Roam This Way. https://www.roamthisway.com/post/malaysian-ghost-towns-series-pekan-papan

Janet. (2023). Papan: Forgotten Row Of Heritage Shophouses In A Perak Town With A Hidden WWII History. TheSmartLocal Malaysia – Travel, Lifestyle, Culture & Language Guide. https://thesmartlocal.my/papan-perak/

Hamastura, M. (1986). Penempatan kaum mendailing di Perak tengah hubungan di antara kehidupan sosial, senibina dan perancangannya/Hamastura Mahayuddin (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Teknologi MARA).