According to the Oxford Dictionary, batik is a technique for printing patterns on fabric using wax to block the areas that shouldn’t be coloured. In this process, wax, a solid substance typically derived from fat or oil, is used to create intricate patterns and designs.

Meanwhile, Kamus Dewan describes batik as “kain yang bercorak (dilukis atau ditera dengan lilin dan dicelup),” which translates to fabric with patterns created by painting or stamping with wax and then dyeing.

Furthermore, as detailed in these journals (1 & 2), the term batik is believed to have its origins in the Javanese words ambatik or tritik. The common suffix tik in both words translates to creating little dots. Ambatik signifies the act of drawing, writing, painting, or dripping. Batik patterns can be created using various methods, including a carved block, a screen, or manual hand strokes.

Malaysian batik is an intricate textile art with a history that spans centuries. This unique form of artistic expression has not only won the hearts of Malaysians but has also gained international recognition. In this blog post, we’ll delve into the history of Malaysian batik.

Understanding the origin of batik is a complex puzzle, as scholars have yet to pinpoint its exact source and antiquity. Different experts offer varying perspectives on the history of this ancient craft.

For example, Arney (1987) highlights the diverse regional classifications of batik in the Malay Archipelago, showcasing the global richness of batik techniques. Keller (1966) proposes that batik’s age could be at least 2,000 years old, though its true beginning remains a mystery.

Before exploring the beginnings of Malaysian batik, it’s crucial to examine batik artefacts from different locales. Raffles (1817) mentions batik as a common element in Javanese arts and crafts, particularly in the creation of textile garments.

Mijer (1919) adds that the origin of batik in Java remains uncertain. Nevertheless, evidence from 13th-century temple ruins in Indonesia suggests that batik was already established in Java during that period.

Although it’s evident that batik has a lengthy history in Java, its precise origins remain elusive. Some scholars, like Steinmann (1958), Kafka (1959), and Robinson (1970), propose that batik may have originated in India or China, spreading to various regions afterward. On the other hand, Spee (1982) suggests that batik probably had its roots in Asia before disseminating globally over time.

Malaysia plays a significant role in the batik narrative due to its strategic position as a trading hub. Batik, along with other cultural traditions, likely made its way to the Malay Peninsula through trade and cultural exchanges.

Swettenham (1910) documented a conversation about batik in Malay, signifying its presence in the region. Dennys (1894) observed the use of Javanese batik sarongs among Malay communities, emphasising their cultural and aesthetic significance.

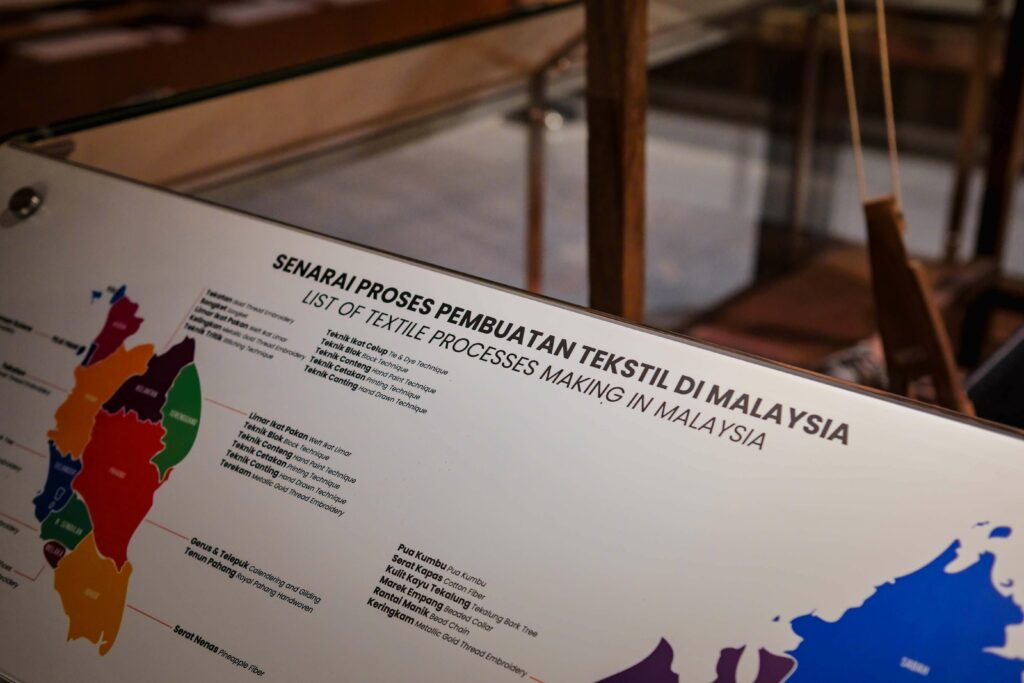

While the exact origin of batik remains shrouded in mystery, this craft boasts a rich history in Southeast Asia, especially in Indonesia, which is renowned for its high-quality batik products. Malaysian batik, influenced by Java, continues to thrive in states like Kelantan and Terengganu, where traditional techniques like tie-dye and block stamping are still practiced today.

The introduction of batik and other materials to the Malay Peninsula can be attributed to historical trade relations. These trade connections between the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia date back centuries, with roots extending to the era of the Malacca Kingdom. Remarkably, these trade ties persisted even during the colonisation of both regions by different European powers.

This enduring relationship is exemplified by a conversation documented by Swettenham (1910), a British officer who studied Malay culture and languages, showcasing a dialogue about batik between a seller and a buyer at a bazaar. In the notes section of his book, Vocabulary of the English and Malay Languages, Swettenham provided an illustration of a conversation involving batik:

Âpa angkau jûal di-sini?

What do you sell here?

Sahya mau bli kain sârong bâtek, bûata-an Jâwa, bûlih-kah dâpat di-sini?

I want to buy some sarongs, Javanese, can I get them here? (p. 213)

This historical context underscores the deep-seated cultural and trade connections that have contributed to the rich tapestry of batik’s history in the region.

Thank you for reading, and lastly, here’s another fascinating piece of Malaysian batik history that you’ll find interesting. In the 1970s, batek was the common term for batik in Malaysia until it was standardised to batik in the 1980s.

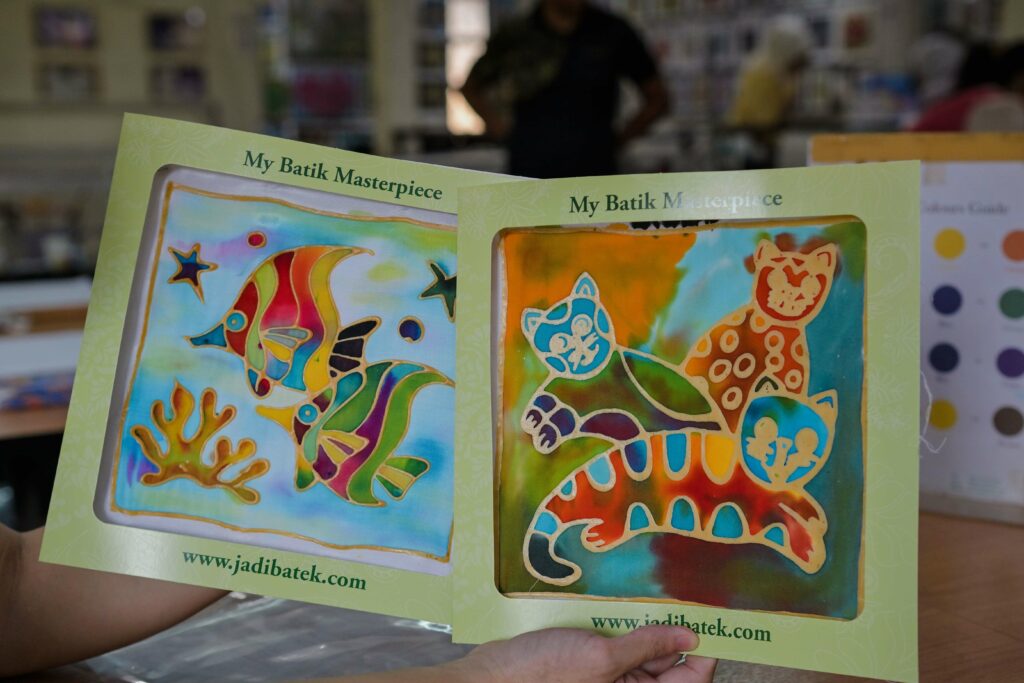

Jadi Batek was the sole batik shop in the Bukit Bintang area during the 1970s and 80s, making it one of Kuala Lumpur’s most popular batik and souvenir shops. Both locals and tourists would visit Jadi Batek to purchase batik shirts before heading to Genting Highlands, where wearing batik attire was mandatory to enter the casino.

References:

Akhir, N. H. M., Ismail, N. W., Said, R., & Kaliappan, S. R. A. P. (2015). Traditional craftsmanship: The origin, culture, and challenges of batik industry in Malaysia. In Islamic perspectives relating to business, arts, culture and communication: Proceedings of the 1st ICIBACC 2014 (pp. 229-237). Springer Singapore.

Nordin, R., & Abu Bakar, S. S. (2012). Malaysian batik industry: Protecting local batik design by copyright and industrial design laws. International Journal of Business & Society, 13(2).

Syed Shaharuddin, S. I., Shamsuddin, M. S., Drahman, M. H., Hasan, Z., Mohd Asri, N. A., Nordin, A. A., & Shaffiar, N. M. (2021). A review on the Malaysian and Indonesian batik production, challenges, and innovations in the 21st century. SAGE Open, 11(3), 21582440211040128.

Yong, C. (2023). Malaysia Batik | Jadi batek. Jadi Batek. https://jadibatek.com/batik/

Batik History – MyBatik Kuala Lumpur. (n.d.). https://mybatik.org.my/batik/batikhistory/

Ilya. (2016, May 26). A colorful history of Batik – FAQ. FAQ. https://www.wonderfulmalaysia.com/faq/a-colorful-history-of-batik.htm